|

The Empie Petroglyph Site

THE EMPIE PETROGLYPH SITE, AZ U:1:165 (ASM)The Empie Petroglyph Site (AZ U:1:165 ASM) was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, August 31, 1998. The following paper was published in McDowell Mountains Archaeological Symposium, Publication of Papers Presented March 20, 1999, Scottsdale Civic Center Library, Scottsdale, Arizona. Scottsdale: Roadrunner Publications in Anthropology 10, 1999.

Additional information about the site can be found in Minding A Sacred Place by Sunnie Empie, Boulder House Publishers.

Sunnie Empie

Arizona Archaeological Society, Desert Foothills Chapter

American Rock Art Research Association

Abstract

Within a boulder outcrop in north Scottsdale there is a significant concentration of rock imagery, including rare bas-relief vulvaforms carved in granitic stone, the first reported in Arizona. The ancient people of the American Southwest were skilled solar observers and here, solstices and equinox are marked by solar interaction with circle and spiral petroglyphs. All the features, including the stone cave with a passageway deep into the Earth, relate to the sacred nature of the site and to understanding past ideology. The Empie Petroglyph Site (AZ U:1:165 ASM) was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, August 31, 1998.

Introduction

The moment we first encountered the magnificent outcrop of boulders, we sensed this was a special place. We might have understood our unexpected emotional reaction, had we known anything about sacred sites. Only later would we learn how important the site is to prehistoric rock art, ancient astronomy, and to understanding the ideology of an ancient culture during the time caves provided shelter.

The Empie

Petroglyph Site AZ U: 1: 165 (ASM) is located amidst an enormous outcrop

of boulders in central Arizona where the northern Sonoran Desert foothills

end and the land breaks into the open, gradually descending toward the

arid valley below. The rainfall at 2,340 feet elevation creates a verdant

landscape called Arizona Uplands subdivision of the Sonoran Desertscrub

(Brown et al. 1979; MacMahon 1985) that supports a wide diversity of flora-palo

verde, mesquite and ironwood trees; saguaros, cholla, barrel and hedgehog

cacti; bursage, creosote bush, crucifixion-thorn, graythorn, and catclaw-that

provide sustenance and shelter to a host of desert wildlife.

Rising majestically from the flat desert terrain, the spectacular outcrop

of granitic stone dominates the landscape with its presence. The jumbled

mass of boulders, some as large as 9 m (30 feet), towers as high as a

four-story building and covers almost an acre of land. The boulders have

rested in silent repose upon the Earth and each other since Precambrian

time, the oldest division of geologic time. Their curvilinear forms, created

over the millennia by natural weathering, have a painterly appearance

ranging from a warm buff to the charcoal black of desert varnish with

highlights of terra rosa and a sprinkling of mica.

The site lies on an axis between two mountains-Lone Mountain, a cone-shaped mountain one-half mile south, and one mile north, Black Mountain, a twin-peaked mountain, both of which could have served as a focus of spiritual energy to the earlier inhabitants as many Southwest Indian cultures venerate mountains. The mountain-axis concept deserves thoughtful consideration.

Rock Art and Revelations

Millennia ago, tapping sounds emanated from the granitic stone as ancient artists carved their messages with a hard, lithic chisel and hammerstone. Over twenty ancient bas-relief vulva-form petroglyphs, repesentations of female genitalia, have been identified. The imagery in granitic stone is atypical of petroglyphs in the area that are pecked on smooth stone generally attributed to Hohokam, and the first recorded in Arizona. There are sites reported in southern California (McGowan 1982; Whitley 1997) and Zuni, New Mexico (Stevenson 1905), where there are bas-relief vulva petroglyphs. The site at Mother Rock at Zuni was used as a shrine by couples who visited it to pray and leave offerings before the birth of a child. (Stevenson 1905)

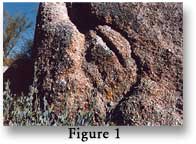

The

images found at the Empie Petroglyph Site were carved on the open vertical

faces of large boulders. Several are low relief (bas-relief), but most

are sculptural and have been enhanced to depths up to 15 cm (6 in) (Figure

1). The ancient artist most often sculpted the image around a natural

fissure in the boulder, perhaps tapping into the power associated with

stone so that it could enter and empower the symbol, strengthening the

life force (Gimbutas 1989). The symbol and the power of stone are brought

together in the art-a meld of material and metaphor.

The

images found at the Empie Petroglyph Site were carved on the open vertical

faces of large boulders. Several are low relief (bas-relief), but most

are sculptural and have been enhanced to depths up to 15 cm (6 in) (Figure

1). The ancient artist most often sculpted the image around a natural

fissure in the boulder, perhaps tapping into the power associated with

stone so that it could enter and empower the symbol, strengthening the

life force (Gimbutas 1989). The symbol and the power of stone are brought

together in the art-a meld of material and metaphor.

Figure 1. Vulvaform petroglyph with natural fissure. © Hart W. Empie

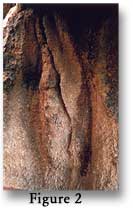

The presence of the vulvaform that is 2.4 m (8 feet) high, 1.2 m (4 feet)

wide and up to 15 cm (6 in) in depth (Figure 2) brings to mind a passage

from Zuni mythology. In their migration story, they named places, followed

by the repetitive phrase, "Here we get up and move on. We come to

stone-lodged-in-a-cleft place; here we get up and move on. We come to

Stone-picture plac e;

here we get up and move on." (Stevenson 1905: 87) Perhaps not this

place although the features are here, but it spurs the question of cultural

connections to sites where bas-relief vulvaform petroglyphs are dominant,

such as at Mother Rock at Zuni's Corn Mountain 200 miles northeast, and

sites in California 200 miles southwest, that exhibit sculptural vulvaforms.

The connections may be far reaching.

e;

here we get up and move on." (Stevenson 1905: 87) Perhaps not this

place although the features are here, but it spurs the question of cultural

connections to sites where bas-relief vulvaform petroglyphs are dominant,

such as at Mother Rock at Zuni's Corn Mountain 200 miles northeast, and

sites in California 200 miles southwest, that exhibit sculptural vulvaforms.

The connections may be far reaching.

Native Americans' ancestors passed this way following a prehistoric trail system leaving evidence of their presence through their rock imagery. As early as 7500 BC, people were migrating across central Arizona (Ortiz 1979). Before 1,000 BC, Cochise Culture clans migrated from California across central Arizona and were part of the Mogollon people in central New Mexico (Schaaf 1996). Archaic lithic tools and projectile points have been found, as well as Hohokam painted potsherds, indicating the site has been used for millennia.

Figure 2. Vulvaform petroglyph 2.4 m (8 feet) high. © Hart W. Empie

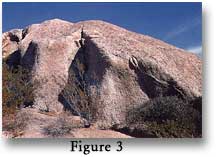

Most of

the vulvaforms are representational, but one is a circle divided with

a slash, one of the earliest known abstractions of the female genitalia

(Giedion 1964). A triangle, also considered an abstract vulva symbol,

appears within the circle (Gimbutas 1989). There are repeated connecting

vulvaforms following a vertical fissure at the top of a west-facing boulder

and three connecting forms along a horizontal fissure. A vulvaform connected

to a serpentine carving represent s

a remarkable integration of forms that are both symbols of regeneration

and renewal (Figure 3). In human life, the umbilical cord is itself a

serpentine connection between the mother and new life (Gimbutas 1989).

s

a remarkable integration of forms that are both symbols of regeneration

and renewal (Figure 3). In human life, the umbilical cord is itself a

serpentine connection between the mother and new life (Gimbutas 1989).

There is an integration of forms within the largest 4.6 m (15 feet) high vulva symbol that rises out of the Earth on the vertical face of a west-facing boulder. In the center is the labial form, and at the top of the fissure, a small perfectly proportioned vulvaform. The space the artist chose to express the concept ought to be looked at as a whole, with the parts in harmony and accord. The art remains precisely where the prehistoric artist meant it to be (Bahn 1998). Neither can symbolism be treated in isolation. Understanding the parts leads to understanding the whole concept.

Figure 3. Vulvaform integrates with serpentine carving. © Hart W. Empie

The symbolic representation of the vulva, the external genital organ of the female, is found in ancient cultures throughout the world from Upper Paleolithic time and has been reported at ancient rock art sites throughout North America and Mesoamerica. The earliest vulva symbols are 30,000-year-old rock engravings near Dordogne, France (Gimbutas 1989), sometimes as simple as a circle with a single mark or slash dividing the circle, or a bisected oval motif (Giedion 1964). The symbol represents the fecundity of the Earth and the productive and creative power of the Earth Mother. Natural formations as well as those that are enhanced or entirely sculpted are considered sources of power and were used in fertility rituals (McGowan 1982). They are part of a universal system of symbols that persist through time and across space and a worldview shared by traditional cultures-visible signs that humankind has always celebrated birth, life, and regeneration.

Native American Paula Gunn Allen, addresses the universal life force in her book, Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions. She writes, "In the beginning was thought, and her name was Woman. The Mother, the Grandmother, recognized from earliest times into the present, celebrated in social structures, architecture, and the oral tradition." (Allen 1992:11). She states, "To assign to this great being the position of 'fertility goddess' is exceedingly demeaning: it trivializes the tribes and it trivializes the power of woman." (Allen 1992:14).

Archaeologist Marija Gimbutas' 1989 book, Language of the Goddess, became a benchmark in evaluating the history of civilization. By reviewing thousands of symbolic Neolithic artifacts and imagery, she established that the symbols represent the iconography of the Great Goddess that arose worldwide in veneration of the laws of Nature. The theme of the symbolism is the mystery of birth, death, and the renewal of life, not only human, but all life. Her extensive research changed the way we look at symbols. Mythologist Joseph Campbell purportedly said that if he had known of her work earlier, he would have written his books differently.

In the

earliest myths, the Earth is alive, as the Goddess-Creatrix herself. With

slight variation in mythology, the vulvaform in veneration of the feminine

divine fits with all our earliest ancestors. All humankind shared the

capacity of using metaphor as a way to express that which could not be

fully understood. We bring with us in our DNA or composition, the heritage

of millennia past, a soul connection to the past. Bill Moyers, television

commentator, eloquently stated in a taped interview with Joseph Campbell,

"What most do not know, is that the remnants of all that 'stuff',

line the walls of our interior system of belief, like shards of broken

pottery in an archaeological site."

The native cultures of the New World were amazingly diverse and prehistoric

contexts are often difficult to establish based on ethnographic data;

however, there is considerable information about the origin and meaning

of the vulva symbol. The commonality of beliefs, including those of ancient

cultures throughout the world, centered on a relationship with Mother

Earth and with all living things. "Tribal systems have been operating

in the 'new world' for several hundred thousand years. It is unlikely

that a few hundred years of colonization will see their undoing. For millennia,

American Indians have based their social systems, however diverse, on

ritual, spirit-centered, woman-focused world-views" (Allen 1992:2).

Rock art remains the single most visible manifestation of prehistoric

ritual (Whitley and Loendorf 1994).

Several hypotheses would be appropriate to the evidence found here at this sacred site: the site was used in ceremonies to enhance fertility of women or, in a broader sense, to celebrate the fecundity and fertility of the Earth itself as it is seasonally renewed; the site was the domain of shamanistic activity, or; the site was the locale to honor the feminine life force of the universe. All elements are part of the entire story of human occupation at the site for millennia. Here is rock imagery that has to do with ideology possibly as distant as Paleolithic and Archaic time, visible signs of an earlier culture's belief that celebrates creation, fertility and fecundity of the Earth. Archaic is not only a period in the Southwest 8400 BC to AD 200, there are ritual and ideological occurrences (Reid and Whittlesey 1997).

The Sacred Becomes Visible

In March

of 1983, a beam of sunlight was noticed moving slowly across the polished

concrete floor. At this time of the year, a ray of sunlight appears through

a narrow split between two 6 m (20') high  boulders

that are the natural west wall of our home. Each day the sunlight extended

farther as it moved slowly upward over a boulder until about 5:25 p.m.

on the Vernal Equinox, it reached the edge of a 76 cm (30 in) spiral in

stone (Figure 4). This also occurs on the Autumnal Equinox.

boulders

that are the natural west wall of our home. Each day the sunlight extended

farther as it moved slowly upward over a boulder until about 5:25 p.m.

on the Vernal Equinox, it reached the edge of a 76 cm (30 in) spiral in

stone (Figure 4). This also occurs on the Autumnal Equinox.

Figure 4. Equinox Solar interaction at edge of spiral. © Hart W. Empie

The Southwest's

earliest inhabitants were skilled solar observers and marked cyclical

events in stone. Perhaps as high as 10 percent of rock art sites in the

American Southwest have an association with a solstice or an equinox (Loendorf

and Loendorf 1998). Following the astounding revelation at the time of

the Vernal Equinox, we anticipated what might occur at a circle petroglyph

on the northeast edge of the site. This petroglyph is surrounded by four

triangular points, a design also seen in the earliest Sikyatki pottery

(Fewkes 1895).

When the Sun reaches its northernmost position on the horizon, a narrow pointer of sunlight enters the circle at 6:15 a.m. to mark Summer Solstice. The narrow beam of sunlight expands within an elongated, concave depression until it fully penetrates the center of the circle (Figure 5). The magnificent 1.8 m (6 feet) high symbol celebrates the completion of the Sun's northward journey at the Summer Solstice. The sight is visually stunning in that it required sculpting two large areas of granite to accomplish solar interaction with the petroglyph.

Figure 5. Summer Solstice solar interaction with circle petroglyph. © Hart W. Empie

The place

honoring the Winter Solstice was elusive. When the site was under review

for the National Register of Historic Places, archaeologist Bruce Masse

suggested that a large cavity in a boulder ought  to

be given particular attention. It appeared that the space could have been

a place for offerings to celebrate the return of the Sun. At Winter Solstice,

a pointer of sunlight created between adjacent boulders enters the space

at 3:30 p.m., but remarkably, there is more. The point of light creeps

slowly into the rear of the space, finally to enter a small hole carved

near the ceiling-a mission possible only when the Sun is at its lowest,

southernmost position in the sky (Figure 6).

to

be given particular attention. It appeared that the space could have been

a place for offerings to celebrate the return of the Sun. At Winter Solstice,

a pointer of sunlight created between adjacent boulders enters the space

at 3:30 p.m., but remarkably, there is more. The point of light creeps

slowly into the rear of the space, finally to enter a small hole carved

near the ceiling-a mission possible only when the Sun is at its lowest,

southernmost position in the sky (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Winter Solstice solar interaction with cavity. © Hart W.

Empie

When the Sun penetrates a symbol or enters caves, it is remarkable that a hole or entry has been created to receive the Sun, a feature that appears to honor the procreative power of the Sun. The Sun enters the space, the womb of the Earth, as well as the vulva to symbolize rebirth and renewal (Gimbutas 1989).

Winter is when the Sun's power is at its weakest and seen as dying. Earth sleeps; animals and snakes hibernate; plants become dormant. The return of the Sun's life-giving light and energy continues to be an important time of year to Native Americans who carry on ancient ceremonies-a time to celebrate the rebirth of the Sun, renewal and regeneration of life. At winter Solstice at Zuni, the rising Sun strikes a certain point at the southwest end of Corn Mountain where vulvaform petroglyphs are dominant. Hopi and Zuni clans still have their Sun Priests so it is likely to presume a social organization existed within the prehistoric society that valued the position of the sunwatcher(s) (Zeilich 1985).

Faint carvings on an exposed southwest-facing boulder take on new meaning at Winter Solstice as the rising Sun casts its light at an oblique angle over the stone. On the face of the vast weathered boulder, circles carved in stone as well as vertical grooves side by side and a cupule or slick in the center come into focus. Here, as well as on other boulders, we find entoptic patterns including the grid, parallel lines, curves, and meander lines (see also Whitley 1997). The importance of light and shadow cannot be overstated, particularly oblique lighting that deepens shadow and emphasizes form.

Entering a Sacred Space

On the southwest

side of the boulder outcrop is a cave-like sheltered area. Universally,

the cave symbolizes the womb of the Earth Mother. Notably, the triangular

shape of the portal to this 'cave' repeats the visual language of the

feminine. The portal has been enlarged so that at Winter Solstice, just

before sunset, a shaft of sunlight reaches the rear of the 'cave' where

it enters several small holes along a diagonal fissure. At Summer Solstice, sunlight enters several

cupules in the floor of this shelter.

holes along a diagonal fissure. At Summer Solstice, sunlight enters several

cupules in the floor of this shelter.

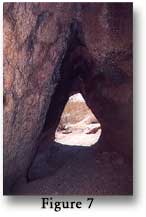

This cave-like rock shelter is shaped like the letter D and measures 1.8 m (6 feet) with similar ceiling height. In the floor, a circular passageway 45 cm (16 in) in diameter goes deep into the Earth (Figure 7). Does it symbolize the passageway that represents to many Southwest Indian tribes the place of emergence into this world? Or does it, as well as the sky opening, represent entrances that conveyed the shaman in his altered consciousness experience (Harner 1990)?

Figure 7. Cave-like shelter with symbolic passageway in the stone floor. © Hart W. Empie

Rock outcrops, rock art sites, and caves are believed to be sources of power and entrances to the supernatural world and prime locations for supernatural quests since the beginning of humankind (Whitley 1997). High on the vertical face of a boulder above the cave-like rock shelter at the Empie Site, a sculptural figure appears as a guardian spirit looking down into the sky opening in the cave.

Elements found here, that are often seen at sacred sites where shamanic activities occurred, include scatters of white quartz and datura (jimsonweed) that grows abundantly on a south-facing slope although rarely seen elsewhere in the area. Shamans in many Southwest tribes used parts of the datura plant as an hallucinatory to induce visions and to enhance their altered consciousness experience and for medicinal purposes. Ethnographic information documents its use by shamans at southern California sites.

The site remains a place of great spirit and presence that neither time nor event has altered. A clump of teosinte springs to life nearby. Datura continues to grow in all its splendor and beauty, a divine essence of an ancient time. Its roots have been recreating here for centuries. The long ivory trumpets raise skyward, saluting the Sun, heralding a new Earth spirit.

Who were the people who had a propensity for stone sculpture and deliberately pecked their messages in stone? The triangular-shaped form that sits prominently on a boulder in front of the Summer Solstice marker is the same abstract form of a head found in ancient art throughout the world. The abstract head's pointed nose and prominent ears together form a V shape. The same form appears as handles or decoration on early Southwest ceramics (see figure 6).

We walk the same path as the Ancient Ones. We sleep beneath the same boulders. Memories of a distant past mingle with the present and reinforce our sense of the interconnectedness of all things. We are privileged to be part of the continuum. Few researchers have the opportunity to know a site so intimately. For the future, we hope that the site will be accessible to the descendants of the first people who passed this way.

Joseph Campbell stated, "One cannot but feel that in the appearance of Gimbutas' volume, The Language of the Goddess, at just this turn of the century, there is an evident relevance to the universally recognized need in our time for a general transformation of consciousness. The message here is of an actual age of harmony and peace in accord with the creative energies of nature." (Gimbutas 1989:xiv).

Perhaps that answers our questions, why us, why now? We give voice, at this time, in this place, to ancient messages that are reappearing after centuries of silence.

* * *

This paper has been presented on our web site to share our findings at this site with other researchers. No photographs or portions of this paper may be used without the expressed permission of the author and photographer. All photographs are copyrighted.

Sunnie Empie has a Bachelor of Art degree from The Evergreen State College with an emphasis in art history. For fifteen years, she has researched archaeoastronomy, rock imagery, and ethnohistory relative to the site. The first site report was presented at the American Rock Art Research Association (ARARA) national conference in Ridgecrest, California, May 1998. Empie has published environmental/nature essays and received an award at the 1997 Pacific Northwest Writers Literary Contest for her nonfiction book, Minding a Sacred Place. The site has been documented photographically by Hart W. Empie, a third-generation Arizonan, who has won awards for his photography. The Empies are members of the Arizona Archaeology Society, Desert Foothills Chapter; and the American Rock Art Research Association.

The Empies continue their research in the surrounding area for vulvaform petroglyphs and for solar interaction with petroglyphs. Please contact us if you have found evidence of petroglyphs, pictographs, or geo-forms that appear as the vulvaform.

References Cited:

Allen, P.

G.

1992 The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions.

Beacon Press, Boston.

Bahn, P.

G.

1998 Prehistoric Art. Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom.

Brown, David

E., Charles E. Lowe, and Charles P. Pase

1979 A Digitized Classification System for the Biotic Communities of North

America, with Community (series) and Associated Examples for the Southwest.

Journal of the Arizona-Nevada Academy of Sciences 14 (Suppl. 1): 1-16.

Empie,

Sunnie.

2001 Minding A Sacred Place. Boulder

House Publishers, Scottsdale.

Fewkes,

Jesse Walter.

1898 Archeological Expedition to Arizona in 1895. Bureau of American Ethnology

17th Annual Report 1895-1896, Part II. Reprinted 1971, Rio Grande Press,

Glorieta, New Mexico.

Giedion,

S.

1964 The Eternal Present I: The Beginnings of Art. Princeton University

Press, Princeton,

New Jersey.

Gimbutas,

M.

1989 The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western

Civilization. HarperCollins, New York.

Harner,

Michael.

1990 The Way of the Shaman. HarperSan Francisco.

Loendorf,

L. and C. Loendorf.

1998 Empie Rock Art Site Evaluation. Ms. on file at the Arizona State

Historical

Preservation Office, Phoenix.

McGowan,

C.

1982 Ceremonial Fertility Sites in Southern California. Museum Papers

No. 14,

San Diego Museum of Man.

Ortiz, A.

1979 Handbook of North American Indians, Southwest, Volume 9. Smithsonian

Institution Press, Washington DC.

Reid, J,

and S. Whittlesey.

1997 The Archaeology of Ancient Arizona. The University of Arizona Press,

Tucson.

Schaaf,

Gregory.

1996 Ancient Ancestors of the Southwest. Graphic Arts Center Publishing.

(s.l.)

Stevenson,

M. C.

1904 The Zuni Indians: Their Mythology, Esoteric Fraternities, & Ceremonies.

Twenty-third Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1901-02. Reprinted

1970 by Rio Grande Press, Glorieta, New Mexico.

Whitley, D. S.

1997 Reading the Minds of Rock Artist. American Archaeology. Vol. 1, No.

3: 19-23.

Whitley,

D. S., and L. L. Loendorf.

1994 Ethnography and Rock Art in the Far West: Some Archaeological Implications.

In New Light on Old Art: Recent Advances in Hunter Gatherer Rock Art Research.

Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Zeilik,

Michael.

1985 Sun Shrines and Sun Symbols in the U.S. Southwest. Archaeoastronomy,

No. 9: S86-S96. Supplement to the Journal for the History of Astronomy.

| Home | Minding A Sacred Place | About the Author | Empie Petroglyph Site | Contact | |

|

|